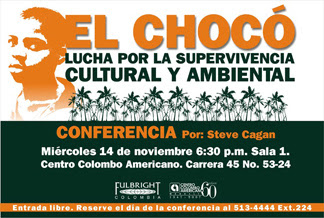

The middle two weeks of November were very busy for me, but not in El Chocó. I spent most of one week in Medellín, where I gave three talks about El Chocó at the Centro Colombia-Americano, one for the general public (I’ve put a copy of the invitation below) and two for Martin Luther King Fellows. And I was able to take advantage of this invitation, prompted by a suggestion from the US Embassy, to visit friends in Medellín and get to know the city a little better.

The Martin Luther King Fellowship is interesting. It’s a grant to help selected Afro-Colombian students move on in their studies and eventually study in the US. My understanding is that it’s funded by the US Embassy and administered by the Colombo-Americano. I’ve spoken to a group in Bogotá and in Medellín, and soon will give a talk to a group here in Quibdó.

After the question and answer period following each talk, I put the following question to them, and I’ve been struck by the fact that none of the fellows so far has known the answer: Why is there an MLK Fellowship? Where did it come from?

They tend to answer by explaining what they expect the fellowship to do for them; that is, they know the goals of the program. But, I ask them, Why did the embassy decide to do this? Generally, there’s no answer, although one young fellow said, “To honor Dr. King.” My next question is, this program is barely 1½ years old. Why did it take them nearly 38 years after his death to honor Dr. King?

The answer is, of course, that this program grew in response to pressure from the Congressional Black Caucus on the embassy that they “do something for the Afro-Colombian people.” But then the question is, “Why did the Black Caucus act so recently?’ And I’m convinced that the answer is the obvious one: these members of congress acted because they began to feel pressure from people in the peace and justice movements in the US. And why did we begin to pressure them? Because after the conflicts in Central America, US foreign policy seemed very focused on Colombia, which suggested the importance of the country to many of us (it’s worth mentioning that Colombia, which receives so much aid from the US, is one of the few hold-outs in a general leftward swing in South American governments).

After Medellín, I spent nearly a week in Bogotá, invited to be part of a day-long seminar on international exchanges to celebrate 50 years of Fulbright in Colombia, and to spend a morning with a class on photography in the media at the Universidad Nacional—and again I spent time visiting old and new friends there.

The Fulbright event was quite good; it exceeded my expectations. Three panels of three people each. The first panel was on the theme of a conceptual framework for understanding international exchange, and to my delight the presentations were quite critical, and very interesting. I’ve been encouraging the Fulbright folks here to publish the presentations.

My own presentation, in the third panel, was about some considerations about photography as social communication, some traps and issues for people who want to be serious about their photography. It’s an old theme of mine, of course, but it has some particular relevance in the context of communications across cultures. I’ve decided to post it in my web pages (it’s a little long for here). If you want to read it, you can go here to see it—sorry, for the moment it’s in Spanish only, but I hope to translate it into English soon.

Actividades recientes

Las dos semanas en medio de noviembre me resultaron muy llenas, pero no en El Chocó. Pase la mayor parte de una semana en Medellín, donde di tres charlas sobre El Chocó en el centro Colombo-Americano, una para un público general (he puesto una copia de la invitación arriba), y dos para becarios de la Beca Martin Luther King. Y pude aprovechar esta invitación, motivada por una sugerencia de la embajada EEUU, para visitar a amig@s en Medellín y conocer un poco más la ciudad.

La Beca Martin Luther King es interesante. Es una beca para ayudar a un@s estudiantes afro-colombian@s elegid@s a que avancen sus estudios y al fin estudien en EEUU. Tengo entendido que es financiada por la embajada EEUU y administrada por el Colombo-Americano. He hablado a un grupo en Bogotá y en Medellín, y dentro de poco daré una charla a un grupo acá en Quibdó.

Después del período de preguntas que siguió cada charla, les puse la pregunta que sigue, y quedé impresionado que ningun@ de l@s becari@s hasat este punto ha sabido la respuesta: ¿Por qué hay una beca MLK? ¿De dónde surgió?

Tienden a contestar con una explicación de lo que esperan que la beca les vaya a hacer, o sea, saben los propósitos del programa. Pero les pregunto, ¿Por qué la embajada decidió hacer esto? Por lo general, no hay respuesta, aunque un joven dijo, —Para honrar al doctor King. Mi próxima pregunta es, Este programa tiene apenas 1 /2 años. ¿Por qué demoraron casi 38 años después de su muerte para honrar al Dr. King?

La respuesta, por supuesto, es que este programa se desarrolló como respuesta de presiones de parte de la organización de congresistas afro-americanos (the Congressional Black Caucus) a que “hicieran algo para el pueblo afro-colombiano.” Pero luego viene la pregunta, ¿Y por qué el Black Caucus sólo se movió hace tan poco? Quedo convencido que la contestación es la obvia: esos miembros del congreso se movieron porque habían empezado a sentir presiones de parte de gente en los movimientos por la paz y la justicia en EEUU. Y, ¿por qué empezamos a presionarl@s? Porque, después de los conflictos en América Central, la política externa de EEUU al parecer se enfocó mucho en Colombia, el cual a much@s de nosotr@s, indicó la importancia del país (cabe mencionar que Colombia, que recibe tanta ayuda de EEUU, es uno de los pocos países resistentes al movimiento hacía la izquierda en los gobiernos de América del Sur).

Después de Medellín, pase casi una semana en Bogotá, invitado a ser parte de un seminario de todo un día sobre el tema de intercambios internacionales para observar 50 años de Fulbright en Colombia, y a pasar una mañana con una clase sobre la fotografía en los medios de comunicación a la Universidad Nacional—y otra vez ocupé tiempo visitando a viej@s y nuev@s amig@s allá.

El evento Fulbright fue bastante bueno, mejor que había esperado. Tres paneles de tres personas cada uno. El primer panel trató el tema de marcos conceptuales para entender intercambio internacional, y quedé contento con las presentaciones, que fueron bastantes críticas, y muy interesantes. He estado animando a la gente del Fulbright acá a publicarlas.

Mi intervención, en el tercer panel, fue sobre unas consideraciones en cuanto a la fotografía como comunicación social, unos escollos y asuntos para gente que quiere ser sería en su fotografía. Es un tema viejo mío, por supuesto, pero tiene una relevancia en el contexto del tema de comunicaciones a través de las culturas. Si la quieren leer, pueden ir a verla acá. Por el momento, sólo en castellano, pero espero traducirla al inglés dentro de poco.